This is the second article in the remote work and productivity series, focusing on methodologies, best practices, and approaches that can be used to improve productivity.

Series Motto: Being busy is not the same as being productive

In the first article of the series, we explored how our brains function and the biggest limitations to staying focused and productive. In essence, our brain is not very good at multi-tasking or context switching and tends to be easily distracted. To become productive, we must first mitigate those obstacles.

The goal of this post is to discuss, in a very basic way, various approaches and methodologies that can be used in daily life to make our workspace more productive. One disclaimer before we proceed: there is no golden bullet or ideal solution to how people should work to be more productive because everyone’s brain is a little different. The only way to find the solution that suits you the best is to experiment and try different approaches, mixing them, sticking with some of them or coming up with a completely new idea. This article presents different methods to help people ease into the journey of better productivity.

Deep Work

As we discussed earlier, our brains like to be fed with “quick-win candies”, which leads us to focus too much on small, repetitive, easy tasks that provide quick results. However, these easy tasks do not often contribute to bigger projects or do not add much long-term value.

The concept of “deep work” can be understood as the ability to focus on longer, harder tasks that are not easy to complete but offer high value. Most of the methodologies we discuss in this post aim to enable deep work.

In simple words, deep work can be treated as a block of uninterrupted time spent on a single task. Usually that block involves 60 to 120 minutes of constant work. After each block, a break is recommended (i.e. a walk), with no more than three deep work blocks per day. Anything more might result in a drop in productivity and focus because the brain becomes overtaxed. The most important aspect is that the block is uninterrupted. Research says that a single context switch requires around 23 minutes for a person to regain full focus!

The rest of this article will try to explain how to create time and space for those three deep work blocks. We will also cover how to decide what we should work on during that dedicated time and how to squeeze in additional tasks between those blocks.

Planning

The planning phase is a frequently skipped step when discussing productivity. As we’ve mentioned before, our brains have limited short-term memory capacity, which can lead to context-switching and that nasty feeling that you’re forgetting something. The goal of planning is to remove the need to constantly think about non-important tasks and allow our brain to focus on that single, important task.

For the scope of this article, we focus on short-term planning only. The monthly and yearly planning perspectives will be covered by our next blog post.

Daily or weekly planning can involve different approaches or strategies. For example, a common practice is called Weekly-5, Daily-3. The idea is that we select the five most important tasks we want to complete by the end of the week that require deep focus. Ideally, only a single task should be assigned to a single day but it’s not a necessity.

Once we block time (more on that later) for deep work on our selected tasks, we can think about additional tasks that can be added to the Daily-3 list. The Daily-3 list should reflect what is currently required, since flexibility is one of the keys to becoming productive. We do not want to push any of the predefined Weekly-5 tasks unless absolutely necessary (i.e., a critical task came in during the week). Taking the time to plan at the end of each day allows us to set up our next day for success. We can evaluate our progress, tweak our Daily-3 list, and adjust our goals accordingly.

Time Management

One of the best and hardest ways to boost productivity is to practice time management. Different methodologies emphasize different aspects of time management, which means time management is a skill that can be customized for individual success. Some prefer a very flexible schedule whereas others favor a fully booked calendar. By testing different approaches, we can find our ideal balance between blocked and flexible time. Below are various concepts that can be utilized:

Theme of the Day

This approach is interesting but can be hard to implement properly. The idea is that each day of the week has a main theme, and we try to group tasks that are as close to that theme as possible. For example, one day we put more focus on feature discussion. Another can be dedicated to Design work, while yet another can focus on marketing or team management.

Obviously, it is impossible to work only on tasks from the given theme but this approach helps in the planning phase. Instead of having one to two meetings each day, separated by 15-30 minute breaks, we can try to schedule all calls in 1-2 days at most. This frees up the rest of the week for deep work blocks.

Time Blocking

Time blocking is a similar concept to the theme of the day but on a smaller scale. The idea is to group similar tasks and assign each group to a time slot (various in length). Time blocking is a major element to successful deep work, by reserving blocks of time in the calendar to protect and preserve focus. This method also typically includes a 30-minute window each day for emails and asynchronous communication. Some methodologies use time blocking to the extreme, with all blocks on the calendar filled. However, this can be quite dangerous since there is no flexibility in the schedule to accommodate schedule changes, crises, or shifting priorities.

Flexible Schedule

This approach is heavily used in the Getting Things Done® methodology created by David Allen. Instead of scheduling tasks, we store lists of tasks that are organized by area, type, time/effort requirement, etc. (whatever dividers make the most sense for you). Whenever a task is finished, we select the next most relevant task from the list given the actual circumstances. When properly executed, this approach can massively boost productivity as well as the number of tasks that can be completed during the day. It can also be combined with time blocking for deep work, for those who need a bit more structure to support focus.

Task Management

Another method to support productivity is through Task Management. Every single day brings new tasks that we must handle. These sudden tasks can become a huge productivity killer. They take up valuable space in our short-term memory, pulling our attention from more important tasks. Fortunately, there is a simple, generic way to deal with this problem – notation.

Interestingly, once a task or item is noted (either on paper or digitally), our brain can release the tension and concern associated with it. The burden of remembering has been delegated to the preferred notation medium. Obviously, those tasks should be analyzed, categorized, and acted upon in spare time. This is where the GTD® methodology can really shine.

The details of this methodology are quite complex, and I fully recommend reading the official book written by David Allen. Here are just a few task management tips:

Use sub-folders in the email inbox to support task organization. The inbox becomes the collection area for new tasks that need to be completed or sorted. After sorting the task (email) into the appropriate subfolder, the task leaves our brain and is no longer a source of distraction.

In our spare time (ideally a couple of times per day) we can return to the inbox and sort through ALL the items on the list. The following algorithm should be applied:

- If the task takes less than two minutes, complete it. The idea is that it will take more time and effort to go back to that task in the future. That can be anything like replying to an email, making a short phone call, etc.

- If the task takes more than two minutes, assign how much effort (time) it will require, label the task with appropriate areas or type of activity, assign to a project, etc. Sorting tasks with labels and tags makes it much easier to leverage the grouping strategy during the planning phase. For example, if we assign multiple tasks with the phone call label, we can easily search for these kinds of tasks later. Then we can come up with a plan to complete the calls (all at once in its own block or between larger tasks to offer the brain some variety).

- Assign a ‘milestone’ to each task that takes one of the following values: Next, Scheduled, Waiting, or Someday.

- Next represents all tasks that should be worked on now (without any real time constraint though!).

- Waiting is for tasks that are delegated; we’re waiting for a reply or follow-up.

- Scheduled reflects tasks that are represented in the calendar (meetings, task blocks, etc.).

- Someday designates tasks that we want to track but don’t need to address immediately.

To successfully use this approach, one must be prepared to regularly review all items across all lists, re-assigning and reorganizing as needed.

Task prioritization

In this article, we’ve explained how to organize our time and tasks to plan our days and weeks. One of the hardest parts is how to decide which tasks are important and prioritizing them. There are many ways to accomplish this feat; here are just a few of them:

Eisenhower’s Matrix

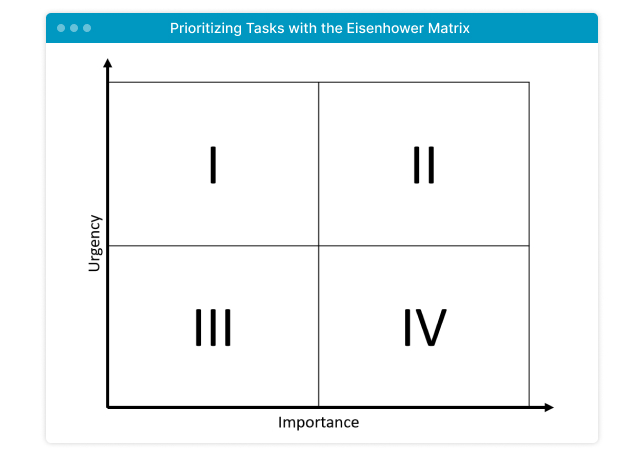

The name of this approach comes from a former president of the United States. The matrix has two axes – Urgency and Importance – and represents four different types of tasks.

- Urgent but not Important – these tasks can be delegated or do not require deep focus but may have a higher priority.

- Urgent and Important – critical tasks that should be addressed as soon as possible.

- not Urgent and not Important – these tasks should be deleted and not worked on at all (if possible). Lowest priority.

- Important, not urgent – tasks that have long-term value and require planning.

In an ideal world, we would work mostly on important tasks rather than urgent ones (a pitfall of urgency). Of course that’s easier said than done, but this chart can serve as a guideline.

In some literature on the Eisenhower Matrix, the following naming conventions for each quarter may appear (the 4 Ds):

- Delegate

- Do

- Delete

- Decide

These conventions provide a shorthand code to help allocate and label tasks appropriately.

Impact/Effort Matrix

This approach is similar to the Eisenhower matrix, but Urgency and Importance are replaced by Impact and Effort. This results in the following types of tasks:

- Big gains, small effort – quick, big wins

- Big gains, big effort – main projects

- Small gains, small effort – simple, necessary tasks

- Small gains, big effort – tasks that we want to skip

ABCDE method

The last approach to task prioritization is called the ABCDE method. The idea is to write down the list of tasks and assign each one a letter: A – the highest priority, E – the lowest priority. Different tasks can have the same letter assigned. Once this is done, if multiple tasks have the same letter, we need to add digits. This will result in a list like A1, A2, B1, B2, B3, …, E1, E2, which creates a cascading list of prioritized tasks.

Summary

This post touches on many different ideas and ways to improve productivity, from task management and prioritization to week/day planning and time scheduling. Unfortunately, this is one of the areas where theory is much easier than practice. Experiment with various approaches can help us find what works best.

In the next post, we’ll try to put a wider perspective on productivity and how to fit everything we’ve learned into long-term planning and goals.

Article written by Tomasz Formański